Publications Hub, Public health & Prevention, Systemic health, Article

Periodontitis and diabetes: a two-way street

14 November 2025

Although the two-way relationship between diabetes and periodontitis has been known for more than two decades and is supported by an ever-increasing body of evidence, a lot more needs to be done in terms of collaboration between dental and medical professionals and in educating the public about the steps they can take to improve both periodontal and diabetic health. Hatice Hasturk and Luigi Nibali explain the science and the steps that need to be taken.

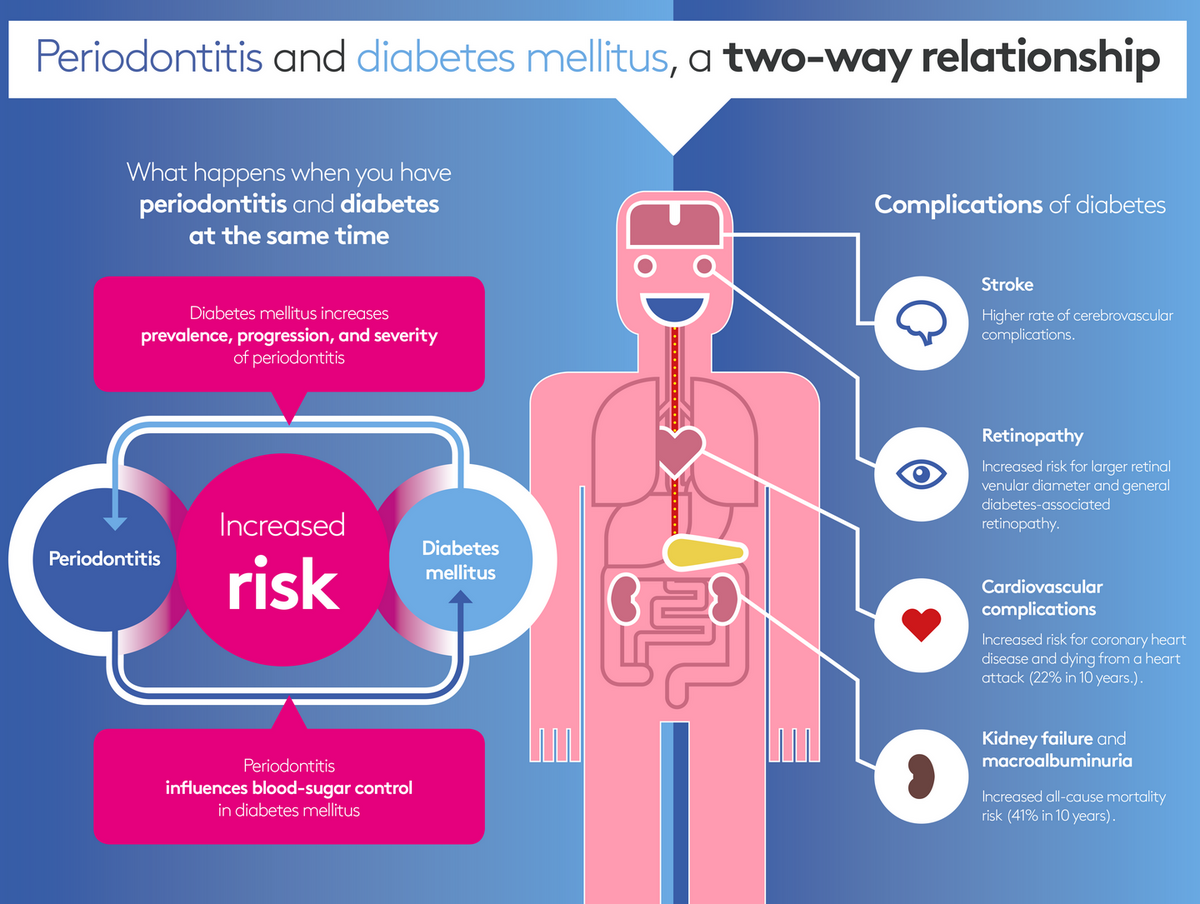

The reciprocal relationship

Based on the evidence, we can confidently say that the two diseases affect each other. In terms of how diabetes affects periodontal diseases, the key factor is how the hyperglycaemia is controlled and how the pathophysiology of the diabetes affects both the immune system and the tissues. There is evidence that periodontal tissues are affected and that these tissues have receptors for proteins or lipids known as advanced glycation end-products, that could make the periodontal tissues more susceptible to glycemia. This promotes inflammatory response in local tissues as we see increased susceptibility to periodontal inflammation and increased severity of the existing disease.

When we talk about how periodontal disease affect diabetes, the key factor is the systemic inflammation. Local inflammation disseminates to the systemic level, and then systemic circulation inflammation can make an individual more susceptible to developing diabetes or can diabetes management worse.

We cannot say that this is a causal relationship. It is more a question of the biological plausibility that the pathways interact with each other. Furthermore, there are some shared risk factors involved in both diseases, such as smoking and poor diet.

When we put all this together, we can confidently say that diabetes affects the periodontal tissues and periodontitis affects or can change the course of diabetes, especially when it comes to the complications of diabetes.

This reciprocal relationship is not just about the onset of diabetes or periodontitis, or about how one can affect the other. It also involves the response to treatment. There is evidence that someone who has diabetes—especially non-controlled diabetes—will not respond to periodontal treatment in the same way as someone who does not have diabetes.

For periodontists, there are several things to consider when we have a diabetic patient. Not just that they are more prone to develop periodontitis, but also that they are less likely to have a good response to periodontitis treatment. We can also say this the other way around: that being able to control periodontitis might lead to a better control of diabetes.

Can treating periodontitis well improve someone’s diabetes? The answer is probably yes. Ten years ago, it would not have been possible to say that. But we now have enough evidence in the literature to say that improving periodontitis can also improve diabetes control. In recent years, some studies have suggested a reduction of HbA1c levels of around 0.4% three or four months after periodontal treatment. This reduction of HbA1c levels has been compared to adding a second drug for controlling diabetes. This is a very powerful message.

It has been shown that a one-percent increase in HbA1c would cause a threefold increase in diabetic complications and vice versa—a one-percent decrease in HbA1c would significantly reduce the diabetic complications, especially all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and other life-threatening diabetic complications.

Even a small change in HbA1c because of periodontal treatment would represent a big benefit to diabetes management.

Raising patient awareness of diabetes and pre-diabetes

As well as performing periodontal treatment, periodontists can also raise their patients’ awareness of diabetes and pre-diabetes. Periodontists and oral-health providers can be part of a team that increases the ability to control diabetes both by periodontal treatment and by encouraging improvements in lifestyle that help both periodontal disease and diabetes.

Informing the patient is very important because often they have never been told about the association between periodontal disease and diabetes, and often they do not have any symptoms suggestive of diabetes.

This connection needs to be explained to them and, if they have not been checked for diabetes, this moment would be a good opportunity. As dentists or dental professionals, we are often the first people who can start having that conversation.

Many studies have shown that a very large proportion of people (between 20% and 40% depending on the studies and settings) who present with periodontal disease have diabetes or pre-diabetes, and many of them were not aware of this, especially those who were pre-diabetic.

This is where there is an opportunity for us as dental professionals to help with detection and kickstart that process, which involves not only taking better care of their gums but also improving their lifestyle and eventually improving their overall health.

People often visit dental professionals more often than other medical professionals, so there is an opportunity to use this to identify potential diabetes patients and point them in the right direction. You could use very simple detection systems like the finger-prick test and then direct the patient to their family doctor depending on what you find.

How to educate patients

We need to listen to patients and understand how they receive this information and what is the most effective way of delivering it, so that they do not feel like you are telling them off or giving them a lecture, but rather that you are giving them helpful information they can use.

We are not experts in nutrition, but we can give them some ideas about the food they should or should not be eating, based on recent research. Even if the amount of information we can give is fairly limited, we can point them in the right direction and motivate them to lose weight and to have a healthy diet.

But this is not easy, particularly when there is so much easily available cheap junk food, while healthy food may be much more expensive.

Another element concerning diet is that people with advanced periodontitis have wobbly teeth and lose teeth. So, they often end up eating food that is less healthy because it is easier to chew and bite, rather than fresh vegetables that may be more difficult to chew.

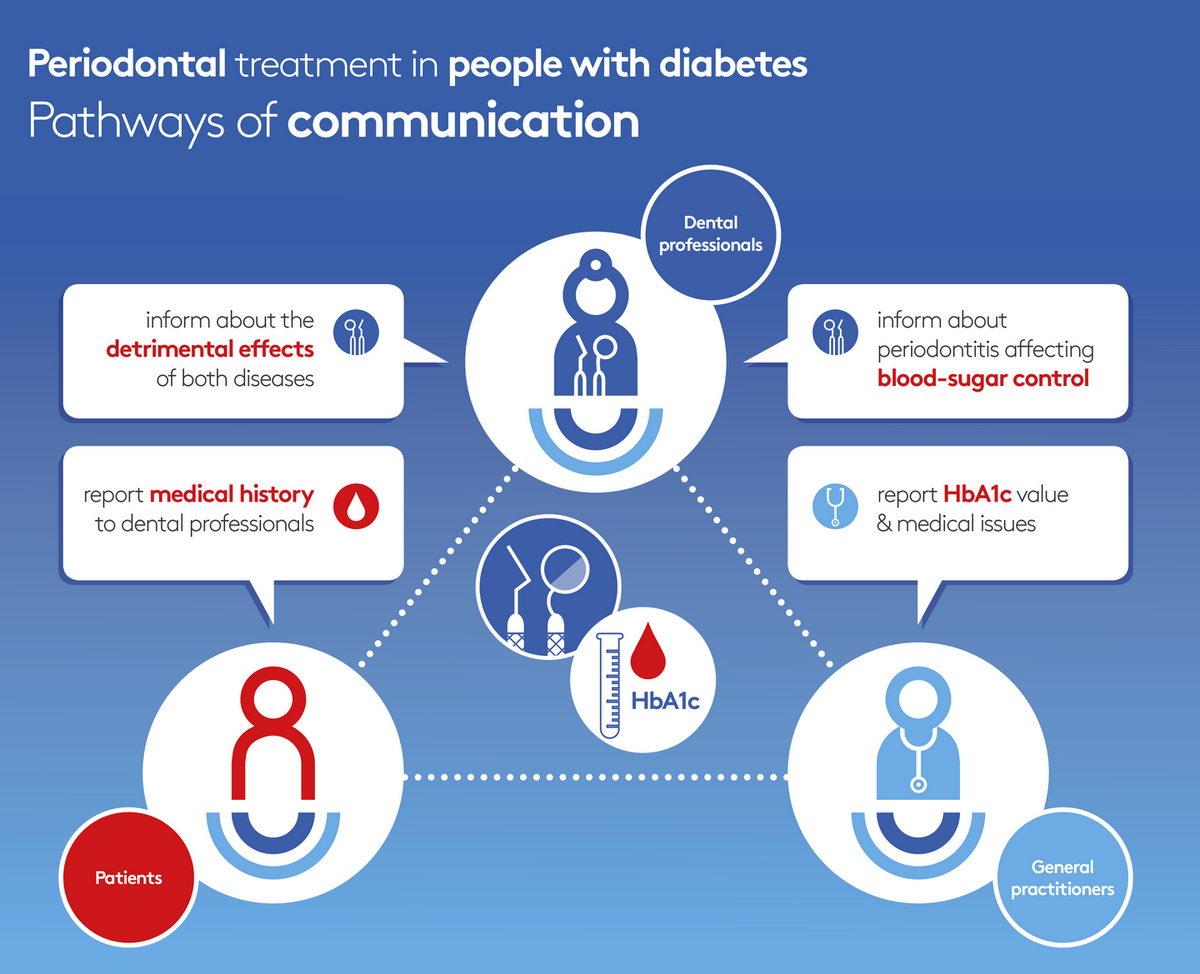

Towards integrated healthcare

Integrated care is not just about dentists sending patients to the general practitioner but also in the other direction—if a doctor has someone with uncontrolled diabetes, they should ask for the patient to have a dental assessment because it is highly likely they will have a dental disease, particularly periodontitis.

The number of medical professionals who understand the importance of oral health is increasing, which is excellent. But there is still a lot of work to do.

The first step is to establish early-screening tools and protocols that might become a standard within the professions, and then implement them in the daily practice of dental and medical colleagues. The second step is to create interprofessional teams and integrated systems, so that when the dentist looks at a patient’s chart they can see when the patient last saw the endocrinologist, when they saw the dietician for counselling, and when they had had an eye exam. And, likewise, the medical person can see when they had a dental visit and when they received dental care.

The importance of prevention

The other important aspect is prevention. Acting very early on in someone’s life—in childhood—is where the best prevention can happen. Childhood obesity is associated with a whole series of dental diseases, such as caries and periodontal disease later in life. Childhood is when you should plant the seeds of good information about lifestyle and diet because this is an opportunity to prevent problems and avoid gingivitis and then periodontitis, or pre-diabetes and then diabetes when that person is in their thirties or forties or fifties.

Technology can help—giving patients targets they can easily see on their smartphone: a certain number of steps, a specific diet, how long they brush their teeth. This can be a powerful way to improve behaviours.

But prevention in the early stages is the thing that would probably make most difference. Investment in the younger generations and in giving the right information will not only reduce the incidence of these diseases later in life but will also save a lot of money from the health service.

The EFP’s work in periodontitis and diabetes

The EFP has already done a great amount of work that has been very effective in raising awareness. In 2017, there was the combined workshop between the EFP and the International Diabetes Federation, which led to joint guidelines and recommendations. And this shows that the diabetes scientific community has accepted that this link really exists and the importance of treating periodontal disease in the management of diabetes.

The EFP also produced the manifesto that highlights the connections between periodontal disease and systemic health and the potential actions to take.

What we need to do now is focus not just on the specialist diabetologist but also break the barrier with the general practitioner. But we should recognize that it is not only about awareness—it is also about resources. There may be GPs that are aware of the potential connection but who maybe do not put any steps in place because they lack the resources or the time to talk about periodontal disease with their patients.

Note: all images in this article are taken from the EFP's Perio & Diabetes campaign.

For further information, visit the EFP's Perio & Diabetes campaign

Bibliography

Botelho J, Mascarenhas P, Viana J, et al. An umbrella review of the evidence linking oral health and systemic noncommunicable diseases. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):7614.

Chapple IL, Genco R; Working group 2 of joint EFP/AAP workshop. Diabetes and periodontal diseases: consensus report of the Joint EFP/AAP Workshop on Periodontitis and Systemic Diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 2013 Apr;40 Suppl 14:S106-12. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12077. PMID: 23627322.

Estrich CG, Araujo MWB, Lipman RD. Prediabetes and Diabetes Screening in Dental Care Settings: NHANES 2013 to 2016. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2019 Jan;4(1):76-85. doi: 10.1177/2380084418798818. Epub 2018 Sep 6. PMID: 30596147; PMCID: PMC6299263.

Genco RJ, Graziani F, Hasturk H. Effects of periodontal disease on glycemic control, complications, and incidence of diabetes mellitus. Periodontol 2000. 2020 Jun;83(1):59-65. doi: 10.1111/prd.12271. PMID: 32385875.

Kocher T, König J, Borgnakke WS, Pink C, Meisel P. Periodontal complications of hyperglycemia/diabetes mellitus: Epidemiologic complexity and clinical challenge. Periodontol 2000. 2018 Oct;78(1):59-97. doi: 10.1111/prd.12235. PMID: 30198134.

Lalla E, Papapanou PN. Diabetes mellitus and periodontitis: a tale of two common interrelated diseases. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011 Jun 28;7(12):738-48. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.106. PMID: 21709707.

Polak D, Shapira L. An update on the evidence for pathogenic mechanisms that may link periodontitis and diabetes. J Clin Periodontol. 2018 Feb;45(2):150-166. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12803. Epub 2017 Dec 26. PMID: 29280184.

Preshaw PM, Alba AL, Herrera D, Jepsen S, Konstantinidis A, Makrilakis K, Taylor R. Periodontitis and diabetes: a two-way relationship. Diabetologia. 2012 Jan;55(1):21-31. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2342-y. Epub 2011 Nov 6. PMID: 22057194; PMCID: PMC3228943.

Sabharwal A, Gomes-Filho IS, Stellrecht E, Scannapieco FA. Role of periodontal therapy in management of common complex systemic diseases and conditions: An update. Periodontol 2000. 2018 Oct;78(1):212-226. doi: 10.1111/prd.12226. PMID: 30198128.

Sanz M, Ceriello A, Buysschaert M, Chapple I, Demmer RT, Graziani F, Herrera D, Jepsen S, Lione L, Madianos P, Mathur M, Montanya E, Shapira L, Tonetti M, Vegh D. Scientific evidence on the links between periodontal diseases and diabetes: Consensus report and guidelines of the joint workshop on periodontal diseases and diabetes by the International Diabetes Federation and the European Federation of Periodontology. J Clin Periodontol. 2018 Feb;45(2):138-149. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12808. Epub 2017 Dec 26. PMID: 29280174.

Simonelli A, Citterio F, Falcone F, D’Aiuto F, Sforza NM, Corrao S, Sesti G, Trombelli L. Effect of Periodontal Treatment on Metabolic Syndrome Parameters: A Systematic Review. Oral Dis. 2025 Jul 2. doi: 10.1111/odi.70018. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40605190.

Simpson TC, Clarkson JE, Worthington HV, MacDonald L, Weldon JC, Needleman I, Iheozor-Ejiofor Z, Wild SH, Qureshi A, Walker A, Patel VA, Boyers D, Twigg J. Treatment of periodontitis for glycaemic control in people with diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022 Apr 14;4(4):CD004714. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004714.pub4. PMID: 35420698; PMCID: PMC9009294.

Stöhr J, Barbaresko J, Neuenschwander M, Schlesinger S. Bidirectional association between periodontal disease and diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of cohort studies. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):13686.

Biographies

Hatice Hasturk, a full professor and the director of the Center of Clinical and Translational Research at the ADA Forsyth Institute. She also holds an adjunct associate professor position at the Boston University School of Dental Medicine and lecture position at the Harvard University School of Dental Medicine. She has published extensively in peer-reviewed journals and has received national and international recognition in dental and periodontal platforms. She is currently an associate editor of the EFP’s Journal of Clinical Periodontology.

Luigi Nibali is a professor and honorary consultant academic lead and director of the EFP-approved postgraduate programme in Periodontology at Kings College London. He is also the co-lead of the Oral Clinical Research Unit at KCL and an honorary professor at Hong Kong University. Professor Nibali has published widely in medical and dental journals and has received several international research prices in Periodontology. He is currently an associate editor of the EFP’s Journal of Clinical Periodontology.