Publications Hub, Classification & Guidelines, EuroPerio, Article

What have we learned since the 2018 classification of periodontal diseases?

09 May 2025

The 2017 World Workshop organized by the EFP and the AAP approved by consensus the current classification of periodontal and peri-implant diseases that has changed the diagnosis and treatment planning of periodontal patients. After seven years in use, it is time to evaluate the classification’s acceptance, use, and efficacy. Mariano Sanz, one of the architects of the classification, offers an overview of its implementation via the EFP’s clinical practice guidelines, while Purnima Kumar considers the latest research in microbiomics which may prompt a rethink on the concept of “aggressive periodontitis”.

In general, the elements of classification have stood the test of time

By Mariano Sanz

The classification of periodontal and peri-implant diseases, which was approved by international consensus at the World Workshop in 2017 and published in 2018, has meant an important advance in the treatment of patients with periodontal and peri-implant diseases. This classification system not only makes it possible to better individualize treatment according to the specific needs of patients, but also to apply more rigorously the scientific evidence on the effectiveness of the different interventions and treatments used in therapy.

The key aspect of this classification system—especially for diagnosing patients with periodontitis—is that it is not only based on the severity and extent of periodontal disease but also assesses the complexity of the treatment and the degree of risk of the patient’s disease progressing after treatment.

In the first case, we use the stage system, which allows us to distinguish the extent of disease and the complexity of the treatment of these patients, enabling us to plan the different therapeutic interventions more adequately and, above all, to inform patients of the expected results—either with periodontal treatment alone or, if necessary, with additional interdisciplinary treatments. On the other hand, the system of grades (A, B, C) allows us to identify the patients at greatest risk and thus to individualise preventive and diagnostic strategies more appropriately.

In general, all the elements of classification have stood the test of time. Today the classification is widely used, not only in the scientific field—where practically all publications use the classification criteria to describe the samples studied—but also in the therapeutic field, where nearly all the official documentation we use to record our patients’ treatments uses the classification criteria. Furthermore, most health authorities, insurance companies, professional associations, and scientific societies have also adopted them officially.

As in any classification used in the medical field, the criteria that distinguish between the different categories cannot be completely precise and, on many occasions, a certain degree of interpretation is necessary, which may vary between professionals. However, recent studies to assess the degree of agreement and repeatability between professionals have provided very positive results (although there will always be borderline cases between the different categories, whose diagnosis requires a certain degree of subjective assessment and clinical judgement).

Controversial aspect

Perhaps one of the most controversial aspects is our current ability to distinguish between gingivitis and stage I periodontitis, because we do not have diagnostic tools that identify minimal clinical periodontal attachment loss. However, technological and scientific advances will soon provide us with much more sensitive and specific tools, and this will allow us to overcome this barrier. And when that happens, the fact that we have pre-established diagnostic categories will be a great advantage.

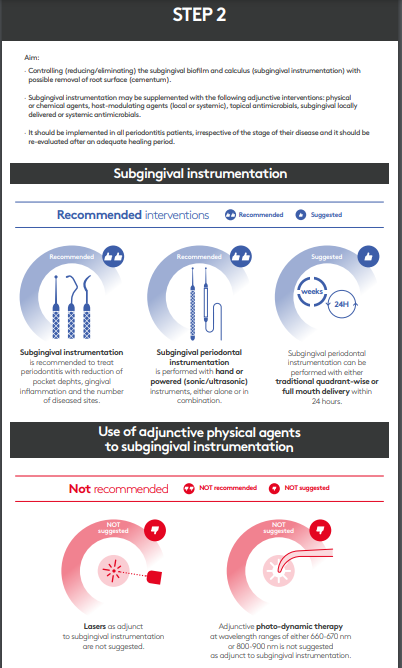

We do not have very reliable data on the global acceptance of the classification and whether its use is widespread among specialists and general dentists, but the fact that health authorities and health service providers have adopted the criteria of the classification suggests that, over time, its penetration will be massive. This is especially important in those countries, mainly in Europe, where the EFP’s clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of these diseases have been adopted—especially in the treatment of periodontitis, stages I, II and III—which are based on the use of the classification to establish the different diagnostic, preventive, and therapeutic recommendations.

This guideline is the most widely adopted, as it is the one that has already been implemented for five years. But the EFP’s more recently published guidelines (on periodontitis stage IV and peri-implant diseases) are now being studied and adopted by different countries, which makes it likely that they will have behave similarly. Thus, the use of the 2018 classification criteria—both for periodontal diseases and peri-implant diseases—will be the norm in the treatment of our patients.

By Purnima Kumar

The 2018 classification of periodontal diseases and conditions abolished the category of “aggressive” periodontitis, replacing it with a disease model for periodontitis based on stages and grades. But the findings from new studies of microbiota in periodontitis patients might suggest that it is time to look at this again.

My talk at EuroPerio11 will be based on two research papers that we have written. In the first paper, we took a hundred subjects and stratified their microbiomes based on the classification’s staging and grading approach. Then we stratified their microbiomes based on the classic definitions from the previous (1999) classification, of localized aggressive periodontitis (LAP), generalized aggressive periodontitis (GAP), and chronic periodontitis.

What we found was that the microbiota of people with chronic periodontitis and people with localized aggressive periodontitis were completely different from each other. On an X/Y map, they sat in two different quadrants. And the people with generalized aggressive periodontitis filled the gap between these two, splitting into two clusters: one was more like the chronic periodontitis group, and the other was more like the localized aggressive periodontitis group.

So, GAP appears to be this conglomerate of diseases: people with the chronic form of the disease who started earlier (early onset chronic periodontitis) and people who had LAP but were not diagnosed and who subsequently developed GAP.

That was our first paper, published in Microbiome in 2021[1]. Then we decided to look at localized aggressive periodontitis and see what is going on there. We looked at a group of 35 subjects with localized aggressive periodontitis and we compared the sites that have disease with those that are free from disease.We took samples from the sites that had disease and from the non-diseased sites, and we compared them between the same subjects.

The paper I will present at EuroPerio11 is called “Janus Man” because it is literally two faced. We are finding that there is a group of people in whom there is no difference between the diseased and the shallow sites microbially. And there is a subgroup where the diseased and the healthy sites are very different from each other.

The role of Aa

We went deeper and we found that in the people where the diseased sites and the healthy sites are very different, that group is dominated by Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (Aa). In the other group, where the deep and shallow sites are very similar, there is Aa, but these people are not Aa dominant.

We took gingival biopsies and sent them off to our colleague, who has all these probes to put into cells and localize where the bacteria are sitting. I am still trying to process the data, because the data is so scary it looks fake! These organisms are sitting inside the nuclei of the cells. These bacteria have entered, they have invaded the cell, and they are not just sitting inside the cell, they are actually sitting inside the nucleus of the cell.

So clearly there is a very aggressive form of the disease—where the organisms enter the nucleus and sit there, creating havoc—and there are other forms of it.

This finding helps me feel a little better about my cases that do not succeed. What we want to see now is if the cases that fail might just be the ones where these bacteria are sitting inside the nucleus and are therefore resistant to anything that we can do and are thus able to cause further damage.

[1] Khaled Altabtbaei, Pooja Maney, Sukirth M Ganesan, Shareef M Dabdoub, Haikady N Nagaraja, Purnima S Kumar (2021). ‘Anna Karenina and the subgingival microbiome associated with periodontitis’,Microbiome, April 30, 2021; 9(1):97. doi: 10.1186/s40168-021-01056-3.

Biographies

Mariano Sanz is Professor and Chair of Periodontology at the Complutense University of Madrid (UCM) and director of the ETEP (etiology and therapy of periodontal and peri-implant diseases) research group. He is also a professor at the University of Oslo in Norway and has received six honorary doctorate degrees from the universities of Gothenburg (Sweden), Coimbra (Portugal), San Sebastian (Santiago de Chile), Buenos Aires (Argentina), Athens (Greece), and the Medical University of Warsaw. He is a past president of the EFP, the Spanish Society of Periodontology and Osseointegration, and the European Federation of the IADR. He has published more than 450 scientific publications.

Purnima Kumar is the William and Mary K. Najjar Endowed Professor of Dentistry and Chair of the Department of Periodontology and Oral Medicine at the University of Michigan, and the principal investigator of the university's Oral Microbial Ecology Laboratory. She has authored over 100 papers and book chapters and serves as the associate editor of Periodontology 2000 and Nature Scientific Reports and as the senior editor of Microbiome. She is the Chair of the AAP’s continuing education oversight committee and was a member of its taskforce for future science. She also serves on the board of directors of the Osteology Foundation and the American Academy of Periodontology Foundation. In addition, she serves on several taskforces for women in science, women in surgery, and women in STEM.

The 2018 classification of periodontal diseases - what have we learned? EuroPerio11 | Vienna | Wednesday 15 May, 13.30-15.00

EuroPerio11 | Vienna | 14-17 May: Information and Registration